Return to the list of my pages written in English about the two envelopes problem

New outline of the Two Envelopes Problem

Skip to Contents

2025/09/19 14:53:47

First edition 2025/09/19

New outline of the Two Envelopes Problem

※This page is an easier-to-read version made of essence of the page titled "An outline of the Two Envelopes Problem" which I made many additions and revisions to since 2015 and which has become difficult to read.

※As result, many parts in this page have addition date or revised date that are earlier than the first edition of this page.

※As result, many parts in this page have addition date or revised date that are earlier than the first edition of this page.

Skip to Contents

Lead section

There are two indistinguishable envelopes containing money, one containing twice the amount of the other. One of the envelopes was then chosen at random and given to you. When you calculate the expected value of the gain by the exchange envelopes using the relation of the amount in the envelope you were given to the amount in the other envelope, you notice that the other envelope is more preferable. The Two Envelope Problem is a problem that demands you to solve a paradox in which the equality of two envelopes is destroyed as soon as one of the envelopes is given to you. There are many different types of questions and no single interpretation for them, so there are a variety of answers flying around. And what's worse is that time is wasted on pointless arguments between people with different interpretations.Common Structure and Variations of Problem Statements

Common Structure

The problem statements for the two envelopes problem consist of three parts: 1) game setting, 2) expected value calculation, and 3) paradox.The part of game setting describes the following:

- There are two envelopes containing money, one of which is twice as much as the other.

- A randomly selected envelope is given to the game player.

- Game player is given the chance to switch envelope

The part of expected value calculation describes the following:

- The expected value of the amount the player will receive as a result of the exchange is greater than the amount the player currently has, so it is advantageous for the player to exchange.

Various paradoxes are described in the paradox part.

For example:

- If the player imagine that he/she had chosen the other envelope instead of the current one, the expected value calculation would indicate that he/she should exchange envelopes, so that each envelope would be preferable to the other.

- etc.

Major variations of the problem statements

Variations on number of players- Only one player

- Two players exchanging envelopes

Variations on exchange opportunities

- Before the player open the handed envelope and confirms the amount of money

- After the player open the handed envelope and confirms the amount of money

Variations on the explanation of how the expected value is calculated

- Explanation with examples of specific amounts

Example: (1/2)$10 + (1/2)$40 - Explanation using a character expression

Example: (1/2)(x/2) + (1/2)2x - Explanation using words only

Example: If I exchange, my money will be halved with probability 1/2 and doubled with probability 1/2

Variations on the paradox presented

- Paradox that both players expect positive return

- Paradox that you should swap regardless of the amount

- Paradox that having whichever envelope, the other is more preferable

- Paradox that switching envelopes due to the switching argument makes you want to switch back due to the same argument

- Paradox that while the situation is symmetrical the argument suggests the other envelope is more preferable

Important examples of problem statements

Earliest published problem statement

I believe Zabell, S. (1988) is the earliest reference that presented the two envelopes problemBelow is a summary I have made of the program statement presented in it.

A, B and C play a game.

C places an unspecified amount of money x in one envelope and a amount 2x in another envelope.

One envelope is handed to A, the other to B.

A opens his envelope and see $10 in it.

A reasons as follows:

"There is a 50-50 chance that B's envelope contains $5. and B's envelope contains $20. If I exchange envelopes, my expected holdings will be(1/2)$5 + (1/2)$20 = $12.50 , $2.50 in excess of my present holdings.

When A offers to exchange envelopes, B agrees since B has already similarly reasoned.

This problem statement has the following characteristics.

A reasons as follows:

"There is a 50-50 chance that B's envelope contains $5. and B's envelope contains $20. If I exchange envelopes, my expected holdings will be

When A offers to exchange envelopes, B agrees since B has already similarly reasoned.

- The opportunity for exchange is given before the player opens the handed envelope.

- Expected value calculation is explained with examples of specific amounts.

- A paradox is presented in that both players expect a positive return.

Early problem statement published by philosophers

I believe Jackson, F., Menzies, P., & Oppy, G. (1994). is the earliest reference that presented the two envelopes problem.Below is a summary I have made of the program statement presented in it.

A person is offered a choice between two envelopes, A and B.

She is told that one contains twice as much money as the other with no information as to which one that is. She chooses A but before opening A she think and get a line of reasoning which suggests that she should have taken B instead.

For the situation between A and B is symmetrical, the merely choosing of A cannot give a reason that she ought to have picked up B instead.

Whether she chosen A or B initially the same reasoning would suggest that she made the wrong choice!

This problem statement has the following characteristics

She is told that one contains twice as much money as the other with no information as to which one that is. She chooses A but before opening A she think and get a line of reasoning which suggests that she should have taken B instead.

Suppose that the amount of money in A is $x.

Then B either contains $2x or $0.5x with same possibility.

Hence the expected value of taking B is 0.5 x $2x + 0.5 x $0.5x = $1.25x, a gain of $0.25x.

This conclusion cannot be right because: Then B either contains $2x or $0.5x with same possibility.

Hence the expected value of taking B is 0.5 x $2x + 0.5 x $0.5x = $1.25x, a gain of $0.25x.

For the situation between A and B is symmetrical, the merely choosing of A cannot give a reason that she ought to have picked up B instead.

Whether she chosen A or B initially the same reasoning would suggest that she made the wrong choice!

- The opportunity for exchange is given before the player opens the handed envelope.

- Expected value calculation is explained using a character expression

- A paradox is presented in that whichever envelope is handed to the player, the other envelope is more preferable.

Problem statement in that expected value calculation is explained using words only

The lead section of the revision at 03:24, 21 June 2016 of the English language Wikipedia article "Two envelopes problem" contains a summary of the problem statement, in which the following expected value calculation is described.

…… It seems obvious that there is no point in switching envelopes as the situation is symmetric. However, because you stand to gain twice as much money if you switch while risking only a loss of half of what you currently have, it is possible to argue that it is more beneficial to switch. The problem is to show what is wrong with this argument.

This problem statement has the following characteristics

- Expected value calculation is explained using words only

- Paradox that while the situation is symmetrical the argument suggests the other is more preferable

Variations in interpretation of the problem

Interpretation imagining two pairs of amounts

With two pairs of amounts as the range of consideration, the expected value is calculated conditional on the amount of money in the selected envelope. The context of the game setting and context of the expectation calculation part are different.

When the problem statement uses a specific amount of money, as in Zabell, S. (1988)'s problem statement, this interpretation is the only possible one.

When the problem statement uses a character expression, as in Jackson, F., Menzies, P., & Oppy, G. (1994). , this interpretation may is one of the possibilities.

Famous examples

- Papers by mathematicians or philosophers

- Zabell, S. (1988)

Nalebuff, Barry.(1989)

Christensen, R; Utts, J (1992),

Jackson, F., Menzies, P., & Oppy, G. (1994).

Chalmers, D.J. - World's oldest Wikipedia article on the two envelopes problem

- The English language Wikipedia article "Envelope paradox" (Revision at 10:55, 26 August 2004) (How to read it)

- Wikipedia article as of 2025

- Section "Bayesian resolutions" of the English language Wikipedia article "Two Envelopes problem" (Revision at 12:44, 22 April 2025)

- The German language Wikipedia article "Umtauschparadoxon" (bearbeitet am 29. November 2024 um 10:56)

- et cetera

- The German language Wikipedia article "Umtauschparadoxon" (bearbeitet am 29. November 2024 um 10:56)

Interpretation imagining one pair of amounts

With one pair of amounts as the range of consideration, the expected value is calculated conditional on the lesser amount of money in the two envelopes. The context does not change through the game setting and the expectation calculation part.

When the problem statement uses a character expression, as in Jackson, F., Menzies, P., & Oppy, G. (1994). , this interpretation may is one of the possibilities.

Famous examples

- Papers by philosophers

- Priest, G., & Restall, G. (2003).

- The earliest Wikipedia article introducing this kind of interpretation

- The English language Wikipedia article "Envelope paradox" (Revision at 01:47, 7 June 2005) (How to read it)

- Wikipedia article as of 2025

- Section "Example resolution" of the English language Wikipedia article "Two Envelopes problem" (Revision at 12:44, 22 April 2025)

- The French language Wikipedia article "Paradoxe des deux enveloppes" (en date du 27 décembre 2023 à 17:21)

- et cetera

- The French language Wikipedia article "Paradoxe des deux enveloppes" (en date du 27 décembre 2023 à 17:21)

Interpretation imagining all pairs of amounts

With all possible pairs of amounts as the range of consideration, the expected value is calculated using mean value of the lesser amount and mean value of the greater amount. in the two envelopes. The context of the game setting and the context of the expectation calculation part are different.

When the problem statement uses words only, as in the lead section of the revision at 03:24, 21 June 2016 of the English language Wikipedia article "Two envelopes problem", this interpretation may is one of the possibilities.

When the problem statement uses a character expression, as in Jackson, F., Menzies, P., & Oppy, G. (1994). , this interpretation is not possible.

Examples

- Writings by mathematicians

- Jeffrey, R. (2004)The following formula is presented as the wrong calculation.… As you think Y equally likely to be .5X or 2X, ex(Y) will be .5ex(.5X) + .5ex(2X) = 1.25ex(X) …

- Personal examples

- My experieneI thought the problem without seeing written problem text, as follows.I imagined the whole possible amounts in the chosen envelope.

↓

I thought it equally likely will be halved or doubled.

↓

In my mind the following formula appers without awareness.ex(Y) = .5 (.5 ex(X)) + .5 (2 ex(X)) = 1.25ex(X).

Each solution corresponding to each interpretation

Solution noticing probability illusion

This solution is for the interpretation imagining two pairs of amounts. And the claims of it are as follows.- Probability should be calculated combining probabilities of selection of pair of amounts and selection of envelopes.

(Expectation formulas using correct probabilities are here) - Probability is not limited to 1/2.

- The exchange of envelopes can be advantageous or not, depending on the amount of money in the envelope chosen.

- The equivalence of the two envelopes can be shown by calculating the average of the expected value of the amount of money in the other envelope over the range of all possible amount of money in the chosen envelope.

- et cetera

In my web page "Interesting web pages about the Two Envelopes Problem" I wrote a list of easy-to-understand web pages that explain the correct probabilities.

Solution exposing tricks which make us tricked by the calculation

This solution is for the interpretation imagining one pair of amounts. The proponents of this solution created diagnostic argument to prove the flaws in the faulty expected value formula.They appear to have tried to uncover the tricks hidden behind the formula that uses the amount in the selected envelope to calculate the expected value of the amount in the other envelope. They then created diagnostic argument based on tricks they discovered.

The tricks that they revealed from the fallacious formula "(1/2)(x/2) + (1/2)2x" may be as follows.

- When reading such a formula, we often confuse the game rules of the two envelope problem with those of the another problem that I call the "Ali-Baba" version problem.

The game of the problem that I call the "Ali-Baba" version problem was introduced in Nalebuff, Barry. (1988) and Nalebuff, Barry.(1989).

In such games, after the amount of the selected envelope is determined, the amount of the other envelope is determined to be either half the amount or double the amount. - When applying such a formula to the problem statement, the meaning of x of the former x/2 and x of the ratter 2x are differ. But this contradiction is hard to notice.

They then created the following diagnostic argument based on the above tricks.

- Checking for contradictions among the fact that the amount of money in the other envelope is determined before the selection of envelope and the use of the symbols "x/2" and "2x"

- Checking for contradictions among the use of the symbols "x/2" and "2x" and the fact that a possible pair of amounts of money is (A, 2A).

I think there is no doubt in their minds that the correct expected value calculation is to calculate the average of the amounts in the pair of amounts. Therefore they doubted the combination of x/2 and 2x in the fallacious expectation formula.

Solution that noticing that the conditions of conditional expected values are ignored

This solution is for the interpretation imagining all pairs of amounts.Solution noticing the "discharge fallacy" (written in Jeffrey, R. (2004))

-

The expected value calculating formla in the problem statement presented in Jeffrey, R. (2004) is as follows..

… As you think Y equally likely to be .5X or 2X, ex(Y) will be .5ex(.5X) + .5ex(2X) = 1.25ex(X) …And as the solution of the problem, it is explained that this formula has been made from the correct formula by discharging conditions of conditional expected values ex(.5X | X>Y) and ex(2X|X<Y).

(X, Y are random variables of the amounts in the selected envelope and the other envelope respectively) -

Based on this explanation、we can get the correct formua as follows:

ex(Y) = .5ex(.5X|X>Y) + .5ex(2X|X<Y).This correct formula is an application of the law of total expectation , and does not conflict the equivalence ex(Y) = ex(X).

My solution

-

When the problem statement uses words only, after reading it we often draw in mind as follows.

Let X and Y be random variables which are assigned to the amount of money in the selected envelope and the other envelope respectively.

Then we get:In the situation that X < Y, Y = 2X and E(Y) = 2E(X).

In the situation that X > Y, Y = (1/2)X and E(Y) = (1/2)E(X). -

Then we often get:

E(Y) = (1/2)2E(X) + (1/2)(1/2)E(X). (← conditions are incorrectly discharged)

-

However, if we have combined the two situations correctly, we will get:

This formula does not conflict the equivalence E(Y) = E(X).E(Y) = (1/2)2E(X|Y=2X) + (1/2)(1/2)E(X|Y=(X/2)).

Mystery that almost people cling to a single interpretation

Each person discussing the two envelope problem has their favorite interpretation and dislikes or abhors other interpretations.

- I have never seen a person who discusses both the probability illusion theory and the tricked by calculation theory as their own theory.

- Both theories are explained in the English Wikipedia article "Two envelopes problem". However it does not mean the existence of an editor who accept both theories. Because the Wikipedia article is compromise of editors.

- The revision at 18:32, 25 October 2005 of the English language Wikipedia article "Two envelopes problem" has lead section discussing the paradox before opening envelope on the interpretation of one pair of amount. And it has section "A Harder Problem" discussing the paradox after opening envelope on the interpretation of two pairs of amount. Therefore at that revision the article kept the principle that each problem statement has one interpretation.

- Fixation on the experienced Eureka effect

- Human who have experienced eureka effect become not able to accept the another solution.

- Analysis method preference

- There are people who are good at evaluating the suspiciousness of each part of a fallacious formula, and there are people who are good at finding errors in the reasoning process that leads to the fallacious formula.

- People have different tolerances for uncertainty of the amount in the selected envelope.

- When recalling the amount of money in a selected envelope, no one can recall both a fixed and a variable image. In other words, some people cannot accept that the amount in the handed envelope can be A or 2A, while others cannot accept that the amount in an envelope they have not yet checked is fixed at X.

Mathematics in the interpretation of imagining two pairs of amounts

Expectation formula – Case of discrete distribution –

Let g(m) be the probability that m is the lesser amount.

Let X be the random variable of the amount of money in the chosen envelope.

Let Y be the random variable of the amount of money in the other envelope.

Then expected winning from a trade are

E(Y|X=x)= ( g(x/2) / (g(x) + g(x/2)) )(x/2) + ( g(x) / (g(x) + g(x/2)) )2x.

For reference.

Let X be the random variable of the amount of money in the chosen envelope.

Let Y be the random variable of the amount of money in the other envelope.

Then expected winning from a trade are

E(Y|X=x)

- Christensen, R; Utts, J (1992),

- Brams, S. J., & Kilgour, D. M. (1995).

- Article "Umtauschparadoxon" (am 14. Juni 2014 um 08:43) in the German language Wikipedia

(This reference was added on March 13, 2016)

Expectation formula – Case of continuous distribution –

Let g(m) be the probability density function that m is the lesser amount.

Let X be the random amount of money in chosen envelope.

Let Y be the random amount of money in the other envelope.

Then the random variable of the conditional expected value of the other amount on the condition that X is the chosen amount is as follows.

E(Y|X)= (g(X) / (g(X)+(1/2)g(X/2)) )2X

+ ((1/2)g(X/2) / (g(X)+(1/2)g(X/2)) )(X/2).

↑ Revised on May 3, 2018, November 4, 2018.

For reference.

Let X be the random amount of money in chosen envelope.

Let Y be the random amount of money in the other envelope.

Then the random variable of the conditional expected value of the other amount on the condition that X is the chosen amount is as follows.

E(Y|X)

↑ Revised on May 3, 2018, November 4, 2018.

- Chalmers, D.J. 1994

- Broome,John.(1995).

(This reference was added on August 14, 2016) - Brams, S. J., & Kilgour, D. M. (1995).

- Barron, R. (2006).

(This reference was added on March 13, 2016) - Article "Umtauschparadoxon" (am 14. Juni 2014 um 08:43) in the German language Wikipedia

(This reference was added on March 13, 2016) - A web page titled "NaClhv: The two envelopes problem and its solution"

- An answer for a question "If you have two envelopes, and ..." at a question site "Mathematics Stack Exchange"

(Asked by terrace on Oct 8, 2014. Answered by robjohn♦ on Oct 9, 2014.)

(This reference was added on May 3, 2018)

- Using the relation of the cumulative distribution functions of these amounts. (e.g. German language Wikipedia article "Umtauschparadoxon" (am 14. Juni 2014 um 08:43))

- Drawing the graphs of these probability density functions. (e.g. A web page titled "NaClhv: The two envelopes problem and its solution")

- Approximating the probability on an infinitesimally small interval of the each amount by f(b)×db and g(a)×da (e.g. An answer for a question "If you have two envelopes, and ..." at a question site "Mathematics Stack Exchange")

Theories for the expected value formula of amount in the other envelope

Not necessarily 1/2

(Added on April 6, 2016. Revised on September 4, 2016.)

Let X be the amount of money in the chosen envelope.

Then there is a prior distribution such that

P(X is lower | X=x) ≠ 1/2 and P(X is greater | X=x) ≠ 1/2 for some x.

Popular proof

Then there is a prior distribution such that

Let M be the max of possible amount of money.

Let x be the amount of money in the chosen envelope.

Then if x > M/3, the amount of money in the opposite envelope can not be 2x, in other words the probability is zero or undefined.

For reference.

Let x be the amount of money in the chosen envelope.

Then if x > M/3, the amount of money in the opposite envelope can not be 2x, in other words the probability is zero or undefined.

For reference.

Not always 1/2

Let X be the amount of money in the chosen envelope.

Then there is no prior distribution such that

P(X is lower | X=x) = P(X is greater | X=x) = 1/2 for all x.

Proof by Zabell, S. (1988).

Then there is no prior distribution such that

(Added on November 6, 2016)

If P(X is lower | X=x) = P(X is greater | X=x) = 1/2 for all x, then

either the interval [1,2) and R+ would have zero probability mass, or [1, 2) and R+ would have infinite probability mass.

In either case the probability distribution cannot be proper.

Popular proof for discrete distribution of amounts of money.

either the interval [1,2) and R+ would have zero probability mass, or [1, 2) and R+ would have infinite probability mass.

In either case the probability distribution cannot be proper.

If P(X is lower | X=x) = P(X is greater | X=x) = 1/2 for all x, then

there are amount a such that sum of P(X=2n × a) diverges, and the probability distribution cannot be proper.

(↑ Revised on April 7, 2016 and April 24, 2016)

One more proof for discrete distribution of amounts of money.

there are amount a such that sum of P(X=2n × a) diverges, and the probability distribution cannot be proper.

(↑ Revised on April 7, 2016 and April 24, 2016)

Let g(x) be the probability of the event "The pair of amounts of money is x and 2x".

Thenlimx→∞ g(x) = 0.

Therefore for some amount of money x,g(x/2) > g(x) .

For reference.

• A blog page "The Universe of Discourse : The envelope paradox".

Is this proof by me for continuous distribution of amounts of money correct?

Then

Therefore for some amount of money x,

For reference.

• A blog page "The Universe of Discourse : The envelope paradox".

Let g(x) be the probability density function of the event "The pair of amounts of money is x and 2x".

IfP(X is lower | X=x) = P(X is greater | X=x) = 1/2 for all x, then g(2x) = 2g(x) for all x .

Let P(n) = P(2n ≤ x ≤ 2n + 1) for natural number n, thenP(n) = 2nP(0) .

Therefore sum of P(n) diverges, and the probability distribution cannot be proper.

If

Let P(n) = P(2n ≤ x ≤ 2n + 1) for natural number n, then

Therefore sum of P(n) diverges, and the probability distribution cannot be proper.

Switching is not always advantageous

Let X be the random amount of money in chosen envelope.

Let Y be the random amount of money in the other envelope.

Then if the prior distribution has a finite mean, then it is false that E(Y|X=x) > x for all x.

Let Y be the random amount of money in the other envelope.

Then if the prior distribution has a finite mean, then it is false that E(Y|X=x) > x for all x.

(↑ Revised on March 29, 2015)

For reference.

- Zabell, S. (1988)

- Nalebuff, Barry.(1989) (This reference was added on April, 18, 2017.)

- Broome,John.(1995).

- Chalmers, D.J. 1994

Two envelopes are not always equivalent

Let X be the random amount of money in chosen envelope.

Let Y be the random amount of money in the other envelope.

Then for some x, E(Y|X=x) ≠ x.

Let Y be the random amount of money in the other envelope.

Then for some x, E(Y|X=x) ≠ x.

(↑ Added on August 8, 2015)

For reference.

- A web page "Amos Storkey - Brain Teasers: Two Envelope Paradox - Solution" by Amos Storkey.

Switching is not always non-advantageous

(Added on August 15, 2015. The title was revised on March 3, 2019)

For any probability distribution, for at least one value of x, E(Y|X=x) > x.

For reference.

Mean values of conditional expectations of the amounts of money in each envelope are same

This paragraph was revised on August 22, 2015, February 14, 2016, March 7, 2016 and March 20, 2016.

Let X, Y be the random variables which denote the amount of money in the chosen envelope and the other envelope respectively. And let x be the amount of money in the chosen envelope. Then E[E(X|X)] = E[E(Y|X)] .

(↑ Revised on June 21, 2016.)

For reference.

- Article "Law of total expectation" (revision at 06:34, 26 September 2014) in the English language Wikipedia.

- The case of continuous distribution was described in the following articles.

- Chalmers, D.J. 1994

- A web page titled "Dan’s Geometrical Curiosities - Maximizing your earnings with money envelopes: a mathematical riddle"

- A web page titled "NaClhv: The two envelopes problem and its solution"

- Ishikawa, S. (2014).

- An answer for a question "If you have two envelopes, and ..." at a question site "Mathematics Stack Exchange"

(Asked by terrace. Answered by robjohn♦ on Oct 9, 2014.) (This reference was added on June 7, 2017)

- The case of discrete distribution was described in the following articles.

- Wagner, Carl G.(1999).

- The article "Enveloppenparadox" (revision at 13 feb 2014 17:33) in the Dutch language Wikipedia.

Please see a companion page "Two methods for the proof of the equivalence of the envelopes of the two envelopes problem".

In 2016, I found very easy proof for discrete distributions.

|

Let z be an amount of money in the chosen envelope.

Consider a sub probability space which is as follows.

Let denote g(zi) by gi. Then And Then we can show that

I expect that this drawing help us to understand the following calculation which had been done by Chalmers. (↓ corresponding row number column was added on 25,2017.)

|

Related topics

Followings are important topics other than the above. They are which I wrote on the page "An outline of the Two Envelopes Problem" which is the source of this page.

Paradoxical distributions which have infinite mean value

On March 10, 2019, this title was revised.paradoxical distribution

If infinite mean value is allowed, there can be "Paradoxical distributions" that switching the envelopes is always advantageous for all amount of money in the chosen envelope.

Following example is most famous among such distributions.

For reference.

For example, a probability density function "f(s)=1/(s+1)2 for s > 0 " was presented in Broome,John.(1995).

(↑ Added on July 22, 2018)

Addition: (Added on September 15, 2019)

The most famous paradoxical distribution above is a special case of the following distributions.

There is no wonder even if the other envelope is more favorable for an amount of money of the chosen envelope.

But it is paradoxical that the other envelope is always more favorable for any amount of money of the chosen envelope.

Following example is most famous among such distributions.

| pair of amounts | probability |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

· · · |

· · · |

|

|

|

|

· · · |

· · · |

For reference.

- Barron, R. (1989) ← Added on April 7, 2017.

- Linzer.E.(1994).

- Chalmers, D.J. 1994 ← Added on May 31, 2018.

- Broome,John.(1995).

- Brams, S. J., & Kilgour, D. M. (1995).

For example, a probability density function "

(↑ Added on July 22, 2018)

Addition: (Added on September 15, 2019)

The most famous paradoxical distribution above is a special case of the following distributions.

Let r denote a number where 0 < r < 1.

Let n denote a natural number where n ≥ 0 and let (2n, 2n+1) be a pair of amounts of money placed in the two envelopes.

Let X and Y be random variables representing the amounts of money in the chosen envelope and the other envelope respectively.

And consider a probability distribution that the probability of (2n, 2n+1) is rn(1-r).

Then :

Let n denote a natural number where n ≥ 0 and let (2n, 2n+1) be a pair of amounts of money placed in the two envelopes.

Let X and Y be random variables representing the amounts of money in the chosen envelope and the other envelope respectively.

And consider a probability distribution that the probability of (2n, 2n+1) is rn(1-r).

Then :

- If r < 1/2, E(X) converges and E(X) = E(Y). (Not paradoxical)

- If r = 1/2, E(X) diverges and E(Y|X) = E(X|X) for X ≠ 20. (The other envelope is almost always as favorable as the chosen envelope)

- If r > 1/2, E(X) diverges and E(Y|X) > E(X|X). (Paradoxical distribution)

Paradox about the equivalence of the two envelopes on the paradoxical distribution

This paragraph was added on December 19, 2017.There is no wonder even if the other envelope is more favorable for an amount of money of the chosen envelope.

But it is paradoxical that the other envelope is always more favorable for any amount of money of the chosen envelope.

Randomized switching

This paragraph was added on September 19, 2015.If we can play opened version game repeatedly, which is the best strategy?

Some mathematicians study the strategies to earn more on average than the strategy not to exchange any time.They take the condition that the distribution of the amount of money is unknown.

And they study how to decide depending on the amount of the revealed money.

Strategies which use random number are called "Randomized switching".

For reference.

- Cover, T. M. (1987).

- Ross, S. M., Christensen R. and Utts, J.(1994). (This reference was added to this list on June 12, 2016.)

- Samet, D., Samet, I., & Schmeidler, D. (2004).

- Albers, C. J., Kooi, B. P., & Schaafsma, W. (2005). (This reference was added to this list on January 21, 2018.)

- The English language Wikipedia article "Envelope paradox" (Revision at 08:51, 1 August 2005) (How to read it)

(This reference was added to this list on June 25, 2017.) - McDonnell, M.D. , Grant, A.J. , Land, I. , Vellambi, B.N. , Abbott, D. And Lever, K. (2011).

- A web page by Emin Martinian which has a title "The Two Envelope Problem". (This reference was added to this list on July 12, 2015.)

- A blog post "Probability Puzzles" which was posted by Renato Paes Leme to "Big Red Bits". (In this post very simple explanation of the principle of the randomized switching was presented.) (This reference was added to this list on September 6, 2015.)

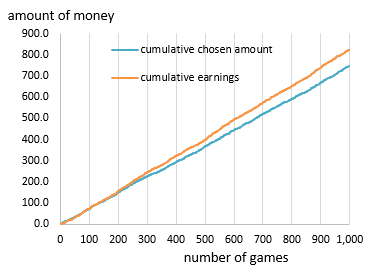

An experiment

On July 12, 2015, referring to the article by Emin Martinian, I tried to see the effect of "randomized switching", and got the following result.

Condition of the experiment

I used Excel.

Result

- Amounts of money have double-precision floating-point values.

- The lesser amount uniformly distributes between 0.0 and 1.0.

- For the chosen amount Y, the decision to switch will be made with a probability

Exp(-Y / 2) .

I used Excel.

Result

An explanation

On July 15, 2016, referring to Ross, S. M., Christensen R. and Utts, J.(1994)., I created a simple explanation.

Let g(x) be a function which has the following characteristic.

And let S1 be a strategy to exchange in probability g(y), and let S2 be a strategy not to exchange

Then S1 will make more earnings than S2.

Why?

Let's think of a pair of amounts of money (a, 2a).

Then g(2a) < g(a).

It means that under the strategy S1, the probability to get the greater amount is(1/2) (g(a) + (1 - g(2a)) . It is larger than 1/2 which is the probability under the strategy S2.

(← Revised on January 5, 2020)

( For detail, please read "An alternative randomized solution" written in the section "Randomized solutions" of the English language Wikipedia article "Two envelopes problem" (Revision at 22:46, 28 December 2019). ) (← Added on January 5, 2020)

Since this argument holds for any pairs of amounts, you can expect that the strategy S1 will give you more gain. (← Added on January 5, 2020)

I had applied this explanation to the above experiment.

If b > a , 0 < g(b) < g(a) < 1 .

And let y be the amount of money in the chosen envelope.

And let S1 be a strategy to exchange in probability g(y), and let S2 be a strategy not to exchange

Then S1 will make more earnings than S2.

Why?

Let's think of a pair of amounts of money (a, 2a).

Then g(2a) < g(a).

It means that under the strategy S1, the probability to get the greater amount is

( For detail, please read "An alternative randomized solution" written in the section "Randomized solutions" of the English language Wikipedia article "Two envelopes problem" (Revision at 22:46, 28 December 2019). ) (← Added on January 5, 2020)

Since this argument holds for any pairs of amounts, you can expect that the strategy S1 will give you more gain. (← Added on January 5, 2020)

g(a) = Exp(-a / 2) and g(2a) = Exp(-2a / 2).

∴ g(2a) = g(a)2.

g(2a) < g(a) because g(a) < 1. (← Revised on July 1, 2017.)

∴ g(2a) = g(a)2.

g(2a) < g(a) because g(a) < 1. (← Revised on July 1, 2017.)

More than one English language Wikipedia article about the two envelopes problem

As of June 16, 2019, the English language Wikipedia has the following articles about the two envelopes problem.

How to read an article which is redirected to the article "Two envelopes problem"

Example: Case of "Envelope paradox"

How to read all articles redirected to the article "Two envelopes problem"

- Envelope paradox

Created on August 26, 2004.

The last redirect to the article "Two envelopes problem" was edited on August 24, 2006. - Two-envelope paradox

Created on February 18, 2005.

Redirected to the article "Envelope paradox" on February 18, 2005.

The last redirect to the article "Two envelopes problem" was edited on December 6, 2005. - Two envelopes problem

Created on August 25, 2005.

No redirect to another article has been edited.

About one month later of creation, the contents was totally replaced. It looks as if there had been different article which has the same title. - Exchange paradox

Created on February 4, 2007

The last redirect to the article "Two envelopes problem" was edited on August 7, 2011.

How to read an article which is redirected to the article "Two envelopes problem"

Example: Case of "Envelope paradox"

| First | Open a page of the English language Wikipedia. |

| Second | Enter "Envelope paradox" as the search key word, and click the search button. |

| Third | If the article "Two envelopes problem" is shown, click the link on the line "(Redirected from Envelope paradox)". |

| Fourth | If the article "Envelope paradox" is shown click the link "View history". |

How to read all articles redirected to the article "Two envelopes problem"

| First | Open the page of the article "Two envelopes problem" of the English language Wikipedia. |

| Second | Click the link "What links here" on the left side bar. |

| Third | If you see a page titled "Pages that link to 'Two envelopes problem'", search the links labeled "redirect page" on the page. |

| Fourth | Click the searched link. |

| Fifth | If a redirected page is shown, click the link "View history". |

Reference

-

Albers, C. J., Kooi, B. P., & Schaafsma, W. (2005)

Trying to resolve the two-envelope problem. Synthese, 145(1), 89-109.

-

Barron, R. (1989)

The Paradox of the Money Pump: A Resolution.

Maximum entropy and Bayesian methods, Cambridge, England, 1988

edited by J. Skilling

Dordrecht : Kluwer Academic Publishers, c1989

pp. 423-428

In this article paradoxical distributions are denoted by the words "Money Pump".

-

Barron, R. (2006).

Continuous Version of the Two Envelopes Puzzle,

listed in the "sources page" of the talk page of the article "Two envelopes problem" in the English language Wikipedia.

-

Brams, S. J., & Kilgour, D. M. (1995).

The box problem: to switch or not to switch.

Mathematics Magazine, 27-34.

-

Broome,John.(1995).

The Two-envelope Paradox, Analysis 55(1): 6–11.

-

Chalmers, D.J.

The two-envelope paradox: A complete analysis?

-

Chalmers, D.J. 1994

The two-envelope paradox: A complete analysis?

-

Christensen, R; Utts, J (1992),

Bayesian Resolution of the "Exchange Paradox"

The American Statistician, Vol.46,No.4.(Nov.,1992),pp.274–276.

-

Cover, T. M. (1987).

Pick the largest number.

In Open problems in communication and computation (pp. 152-152). Springer New York.

-

Ishikawa, S. (2014).

The two envelopes paradox in non-Bayesian and Bayesian statistics.

arXiv preprint arXiv:1408.4916.

-

Jackson, F., Menzies, P., & Oppy, G. (1994).

The two envelope 'paradox'.

Analysis, 54(1), 43-45.

-

Jeffrey, R. (2004)

Subjective probability: The real thing.

Cambridge University Press.

-

Linzer.E.(1994).

The Two Envelope Paradox, American Mathematical Monthly 101. pp.417–19.

-

McDonnell, M.D. , Grant, A.J. , Land, I. , Vellambi, B.N. , Abbott, D. And Lever, K. (2011).

Gain from the two-envelope problem via information asymmetry: on the suboptimality of randomized switching

Proceedings of the Royal Society

-

Nalebuff, Barry. (1988)

Puzzles: Cider in Your Ear, Continuing Dilemma, The Last Shall be First, More.

Journal of Economic Perspectives, 2(2): 149–156.

-

Nalebuff, Barry.(1989)

The other person's envelope is always greener. Journal of Economic Perspectives 3 (1989) 171-181.

-

Priest, G., & Restall, G. (2003).

Envelopes and indifference.

-

Ross, S. M., Christensen R. and Utts, J.(1994).

COMMENT AND REPLY TO CHRISTENSEN, R,, AND UTTS,J. (1992), "BAYESIAN RESOLUTION OF THE EXCHANGE PARADOX," THE AMERICAN STATISTICIAN,47, P. 311: CONMMENT BY ROSS AND REPLY

-

Samet, D., Samet, I., & Schmeidler, D. (2004).

One observation behind two-envelope puzzles.

American Mathematical Monthly, 347-351.

-

Wagner, Carl G.(1999).

Misadventures in Conditional Expectation: The Two-Envelope Problem

Erkenntnis, Vol.51, No.2/3 (1999), pp.233–241

-

Zabell, S. (1988)

One of the additional discussions of Hill, B. M. (1988).

Bayesian statistics, 3, 233-236.

Hill, B. M. (1988).

De Finetti’s Theorem, Induction, and A (n) or Bayesian nonparametric predictive inference (with discussion).

Bayesian statistics, 3, 211-241.

Terms

-

law of total expectation

In brief it is a proposition which states that :If X is a random variable whose expected value E(X) is defined, and Y is any random variable on the same probability space, then E(X) = E(E(X|Y)).For details please see the article "Law of total expectation" of the English language Wikipedia.

Return to the list of my pages written in English about the two envelopes problem